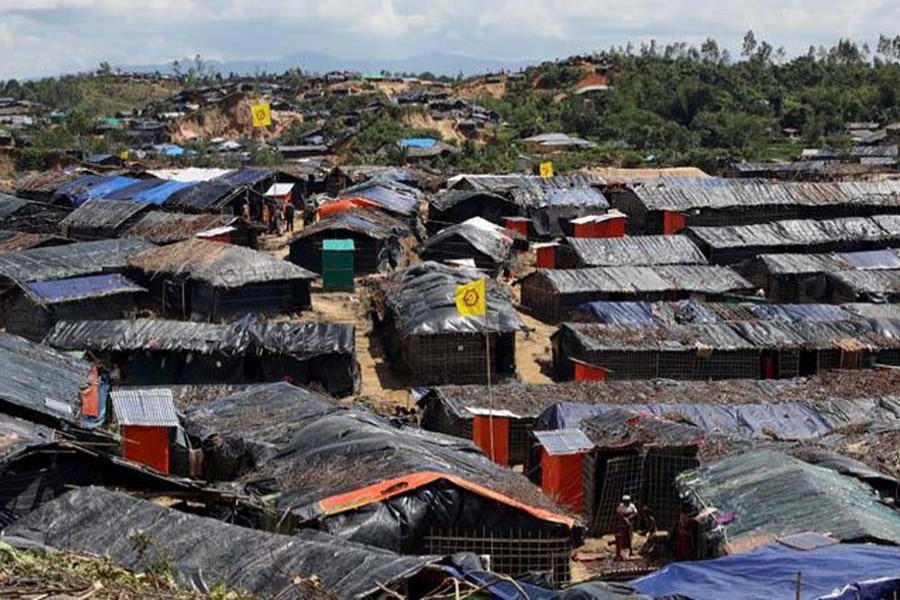

Refugee Camps: Teletalk SIMs for Rohingya families likely

NEWS DESK

Rohingya refugees would soon be able to purchase Teletalk SIM cards as part of the government’s efforts to bridle the ‘growing criminal tendencies’ among the displaced Myanmar citizens and bring them under Bangladeshi network coverage.

At present, the displaced Myanmar citizens use SIMs of two or three operators from Myanmar and Bangladesh, which are obtained by registering illegally under local people.

Crime is increasing every day among the Rohingya community and they use mobile phones for various activities including drug trade, kidnapping and human trafficking, said the representative of police in the meeting.

As the refugees use SIMs of foreign mobile operators, it makes tracking their movements difficult for law enforcement agencies.

So, it is necessary to bring the refugees under local network coverage and stop using Myanmar SIM, as per the decision of the first meeting of the committee to formulate recommendations about the sale of SIM cards to displaced Myanmar citizens in the Rohingya camp.

Every Rohingya family would get a SIM each, according to the minutes of the meeting, which was presided by Abu Hena Mostofa Zaman, joint secretary of the public security division. The meeting took place last month.

The SIM cards would be sold against the ‘Family Counting Number’ from the database prepared by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Subsequently, the committee recommended access to the database for mobile operators and law enforcement agencies.

It would be a challenging task to get the refugees to get used to using the new SIM since the network of Myanmar operators is strong and they use Myanmar SIMs to communicate with relatives, business partners (especially drug trade and other businesses) located in Myanmar, said a representative of the special branch said

But, weakening Myanmar’s network by installing jammers on the border is costly, according to an official of another intelligence agency.

About 1,100 jammers would be needed and each jammer costs Tk 2 crore, taking the total cost to approximately Tk 2,200 crore, he added.

“We are trying to provide them with SIMs to bring them into a system,” Zaman said.

More meetings will be held before a final decision is made, he added.

The length of the Bangladesh-Myanmar border is very small compared with the Bangladesh-India border, said Abu Saeed Khan, a senior policy fellow at LIRNEasia.

“Bangladesh previously was able to stop the signal of Indian network operators. So, the government should utilise the experience of those officials who accomplished that.”

The cross-border criminals, including Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, are comfortably communicating using the network of Myanmar operators.

Before the Rohingya refugee influx to Bangladesh, there was no Myanmar network coverage on the border, Khan said.

“It’s a national security threat to both Myanmar and Bangladesh and this is what the Bangladesh government should escalate to the government of Myanmar,” Khan said, while discouraging giving Teletalk the sole rights to sell SIMs in the camp area.

Private mobile operators protested the proposal as it would be anti-competition.

“The opportunity should be given to everyone. We have the ability to maintain national security issues properly,” said Taimur Rahman, chief corporate and regulatory affairs officer at Banglalink.

Before taking such a decision, the authorities should discuss with relevant stakeholders in the value chain to address the issue holistically, said Hossain Sadat, spokesman of Grameenphone.

“If the public security division thinks that Teletalk should be the lone entity providing network service in Rohingya camps for the sake of national security interest, I can assure Teletalk will do its best,” said Mustafa Jabbar, the telecom minister.

There are 9.6 lakh Rohingyas in the database prepared by UNHCR.